Polyvagal theory and tools to help regulate your nervous system

Have you ever wondered why we handle stress the way we do as humans?

The Polyvagal Theory helps us understand why our body responds to stress in many different ways and it was developed by Dr Stephen Porges. It emphasises the role the autonomic nervous system. It focuses on the function of the Vagus Nerve -the largest nerve in our body, which connects our brain to our gut and has branches of sensory fibres which connect to almost every organ in the body. It is responsible for the regulation of internal organ functions, such as digestion, heart rate, and respiratory rate, as well as vasomotor activity, and certain reflex actions, such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing, and vomiting. It is a major form of communication within our system and extremely important to our survival as a species.

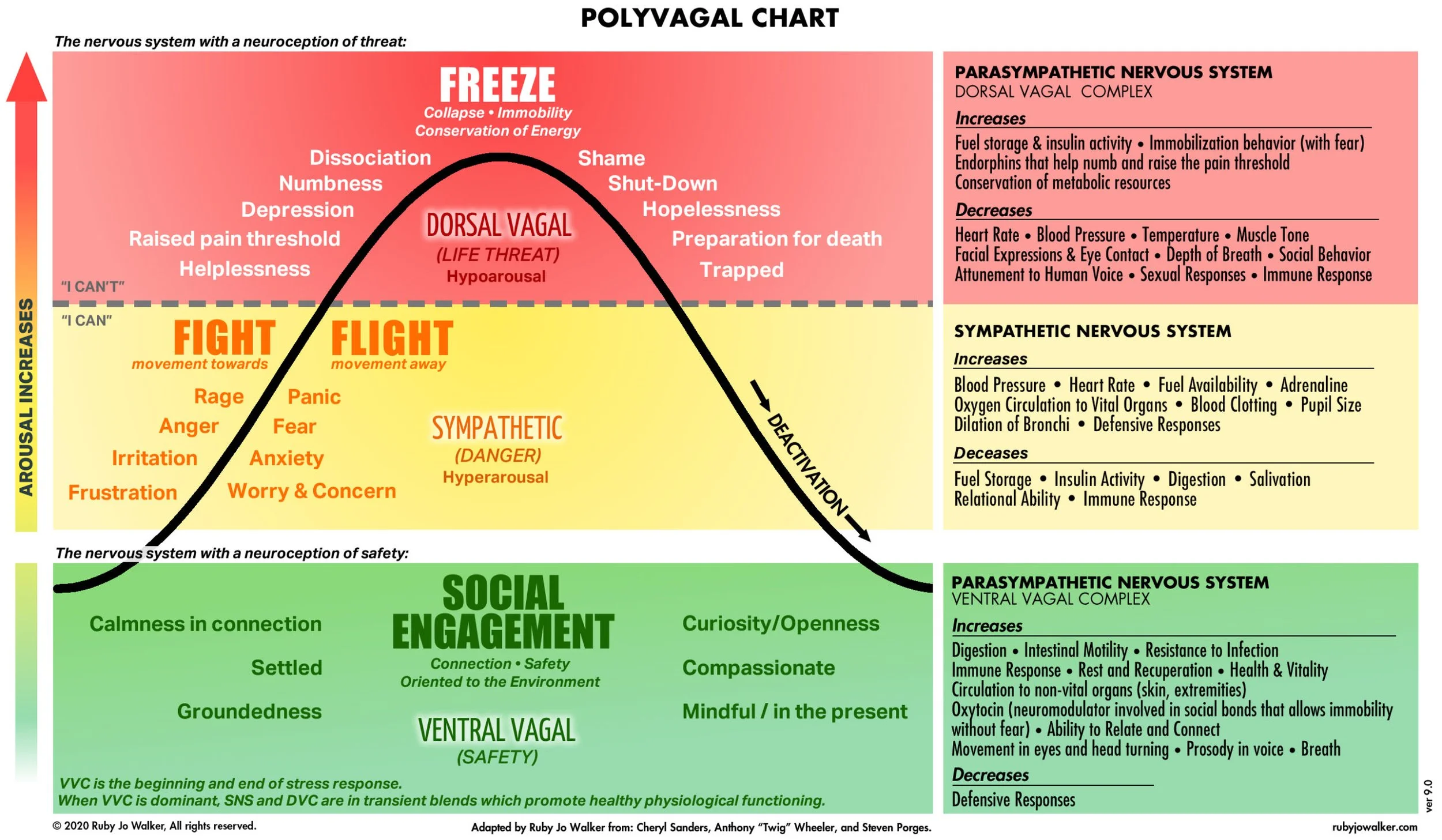

According to Polyvagal Theory our autonomic nervous system shifts between three states:

Ventral Vagal - Stabilisation

Sympathetic- Mobilisation

Dorsal Vagal- Immobilisation

The human central nervous system moves between these states depending on how safe we feel. If we have a healthy vagal response/tone we should move in an out of these states appropriately and efficiently. However, if there has been a lot of trauma in one’s life where they may have experienced a lot of threat, neglect or abuse it may be more difficult to move out of the hyper/hypo arousal states (the good news though is we can strengthen the vagus nerve and our vagal response with tools, strategies and practice over time). When we are in a state of homeostasis or physiological balance the vagus nerve acts as a neutral break- so this means it helps to keep us calm, open and social this is what we call the Ventral Vagal- stabilisation State or we are activating the Parasympathetic Nervous System.

However, if our brain senses danger or threat or we are triggered in any way, the vagus nerve triggers the body to move into our Sympathetic State- mobilisation or Fight/Flight State. Now this is a helpful evolutionary response IF there is a genuine threat, in which case this would help us either fight or run away from the threat, however if there is no genuine threat we may remain in this state feeling our heart race, hands shake or sweat and it may take approximately 20-30 minutes to return to a balanced Ventral Vagal- Stabilisation State.

The Dorsal Vagal- Immobilisation State also responds to cues of danger, but in a different way. It moves us away from connection and into protection. When we experience a cue of extreme danger or life threat we can shut down and feel numb or frozen, we have moved into a Dorsal Vagal State.

When the Dorsal Vagal State is activated we have shifted into immobilisation. This can be seen as freezing, going numb, blanking out, shutting down and dissociating. When the dorsal vagus is activated our parasympathetic nervous system has kicked into gear and is not only slowing us down, it’s moving us into a place of complete freeze or. With animals in the wild we see this response when an animal may move into a ‘feign death response’ when it has been chased and attacked by a predator. All bodily functions shut down and only it’s emergency life support systems are running in the background.

The Effect of Trauma on our Nervous System

When it comes to trauma, Polyvagal theory is important because we know that trauma interrupts our ability regulate our nervous system responses and feel safe in society and in relationships. If one has experienced trauma, one of the challenges they might face is being unable to regulate their autonomic responses like fight, flight or freeze and to feel safe within their bodies and with other people.

In the case of trauma, natural patterns of connection and regulation are replaced with patterns of protection and dysregulation. One might become hypersensitive to detecting threat, constantly scanning the environment for cues of threat and danger.

If we have unresolved trauma it can feel as though we are always in a constant state of hypervigilence ready to move into fight, flight, freeze or fawn. We might also regularly be in states of shutdown, feeling physically and emotionally collapsed or even dissociated and like we are walking around ‘out of our body’.

Trauma and Polyvagal Theory

If you have experienced trauma that left you immobilized, your ability to scan your environment for danger cues can become confused. You may not be able to take in cues of safety as easily. You might instead read cues in your environment as dangerous even if those cues may be seen as neutral to other people.

Depending on our trauma history we may have picked up on a number of interpersonal cues that our nervous system has associated to danger. It could be a slight change in someones facial expression, a particular tone of voice, a body movement or posture even a smell. This can trigger someone with a trauma history to respond in familiar ways that our nervous system learnt to protect ourselves and survive.

Tools for strengthening the Vagus nerve

Deep Slow Breathing

Simply bringing attention to your breath can allow your breathing to begin to slow down and deepen. Slower breathing with a prolonged exhale helps to bring our system into a ventral parasympathetic state. Box breathing is helpful and it involves breathing in for 4 seconds, holding for 4 seconds, breathing out for 4 seconds and holding for 4 seconds and repeat.

Humming

The larynx, or voice box, is connected to the vagus nerve. When you sing, hum, or say “om,” you activate the vagus nerve. Humming will increase your vagal tone.

Safety in Self-Touch

Touch stimulates our vagus nerve and has been shown to reduce depression, pain and stress and also increase immune function. You can experiment with what kind of self touch feels right for you. Some examples:

A hand or two hands over your heart or a hand more in the middle of your chest.

One hand on your heart and one hand on your belly. Again check in if this feels ok for your nervous system.

A butterfly hug- crossing both arms and hugging yourself

Using a self massage tool to massage the back of your neck and scalp

Cold water immersion

Use of cold water immersion stimulates the Vagus nerve, and activates the parasympathetic nervous system. This results in a relaxation response, resetting of the abdominal organs to a resting state, and feelings of well-being. Have a cold shower, fill a bowl with water and ice and dip for face in it or simply grab a bag of frozen peas out of the freezer and hold it on your face or the back of your neck.

Meditation

Meditating can take many forms and does not have to be long and drawn out, but “contemplative practices,” such as meditation and yoga, have been found to bring calm, in part, by activating the vagus nerve.

Gratitude journaling

Sit down before bed or when you wake up and write down three things you’re grateful for, whether they’re big (your family) or something small (your warm, snuggly bed) . Repeat this daily, weekly and you will train your mind to be grateful and this will calm your nervous system.

Grounding yourself

Notice your surroundings. Use your senses what can you see right now? What can you hear right now? What can you smell right now? What can you feel right now? this brings us into the present moment and puts a halt to negative thoughts and worries about the past or future, which in turn cues the vagus nerve to go into it’s ventral vagal state.

Co-regulation and Cues of Safety

Merely resolving cues of danger is not enough to increase our vagal tone. We also need to actively bring in and experience cues of safety in our nervous system. We need to experience co-regulation and connection. Safety can feel triggering as we may have had limited experiences of feeling safe, never felt safe in relationships or had our trust broken.

Therapy is one part of the process of experiencing cues of safety.

Polyvagal theory in psychotherapy offers co-regulation as an interactive process that engages the social engagement systems of an individual. A trauma informed therapist will give you a safe space for co-regulation and focus on helping you to use tools to feel safe and grounded.

Once you can recognise and respect the unique ways your nervous system has worked to help you survive, you can begin to work with self—regulation, experiencing co-regulation and physiological tools such as breathing, humming and cold water immersion to access and deepen ventral vagal activation. Enabling you to feel more stable and grounded in your everyday life.